I’m sorry, it’s been a while since there have been any posts here – some personal matters demanded attention.

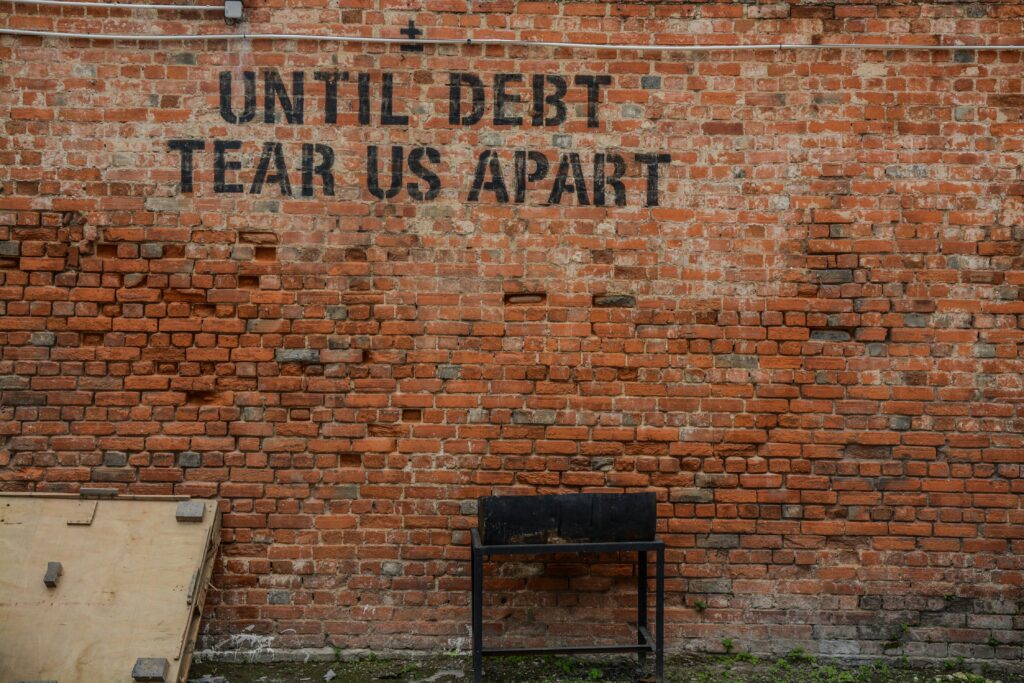

It’s Budget Day in the United Kingdom. The ‘serious’ media, and much of the ‘more interesting’ media, is awash with fevered discussion of how harsh the fiscal punishment will be from the new Labour government. I’d like to talk about fiscal policy in the UK. But this blog is aimed at the dollar’s ‘exorbitant privilege’. What is the connection? Because, friends, American policy settings are of tremendous importance for the price and the quantity of UK government debt despite almost anything the UK government does. This will continue until the UK government renounces or adapts accepted Western policy orthodoxy; a collection of norms that evolved with the dollar system. The fiscal position of the United States is parlous and presents a risk to the fiscal capacity in third countries like the UK.

Thanks for reading ExorbitantPrivilege! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

For all the parochial noise of today’s Budget announcement it will have little long-term or even short-term impact on the amount of UK debt or the cost of that debt. The only question of consequence for UK fiscal policy is how to allocate the funding raised. The UK Budget is simply a domestic redistributive exercise, of little real fiscal consequence. Why? The UK government bonds are a substitute for the US Treasury with some currency risk attached. The ‘exorbitant privilege’ of the dollar determines the scope of UK fiscal policy. Thus, to understand the true fiscal constraints, and futurte risks, to UK policy we may have to account for the fiscal condition of the US. If the fiscal position of the US looks unsustainable, that has serious implications for UK policymakers. We will hear nothing about that today from the UK government. Nor I fear, at any time until the consequences are unavoidable. Then things are likely to get truly unpleasant. This needs to change.

Some fundamental observations. Since 1945, the average yield on UK government bonds has closely matched the average yield on US Treasuries, except for a five-year period between 1974 and 1979. Since 1993, the yield of the two markets has been more-or-less interchangeable.

Nor is this limited to long term bond yields. Monetary policy has been almost identical too, at least since the Global Financial Crisis. Yes, there are deviations. But the short-term deviations prove the long-term rule of co-movement.

The mediating factor throughout this period was the currency, which deviates much more than yields; up to 15 percent in either direction since currencies floated freely in 1971. That may sound a wide margin of fluctuation, but it has defined a bounded range of value for official assets in both currencies. Anything outside that range would be deemed some kind of ‘crisis’ in the currency. UK currency is also bound to the dollar, albeit with a degree of flexibility. A similar situation relates to German bonds (with some more leeway) and Australia, and Canada.

The defining parameters of UK (and other) fiscal freedom is not just the IMF preferred measures such as debt/GDP or interest cost/GDP. These are important moderating constraints locally and provide useful comparison metrics. But it is the fiscal boundaries of the United States that define the capacity limit of everyone. For it is simply impossible for the global ‘risk-free rate’ represented by the US Treasury market to be transferred to any non-dollar instrument. At least until there is some viable, freely tradeable replacement for the US dollar.

Today, as well as mulling the announcement of the UK Chancellor and the fiscal outlook offered by the Office of Budget Responsibility, let’s consider the United States which may have a much more profound long-term effect on the acceptability of any Western government debt. The conclusions are not at all pleasant. Nor are current projections likely to be

The US Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimate the fiscal deficit at around 7% of GDP for 2024. They further estimate the deficit will continue at a similar level for the next 10 years. Both Mandatory outlays (programmes which cannot be cut) and Net Interest payments are expected to rise. Mandatory outlays (highlighted as line number 1 in the table) are currently 85% of total US government revenues and are expected to decline to ‘only’ 79% of total revenues in 2029, a decline predicated on a rise in income tax receipts as a percentage of GDP of almost 2% of GDP. If we think politics are currently fractious in the United States, wait till working people are required to pay more for the mandatory Federal programmes.

And that is the easy bit. The only reason budget deficit is projected to remain at ‘only 6%’ of GDP for the foreseeable future is because Discretionary outlays decline. This means an assumption that both Defence spending and especially Non-Defence discretionary spending will be cut (as a % of GDP). Consider non-defence discretionary spending includes education, transportation, income security, veterans’ health care, and homeland security. We are asked to believe geo-political tensions will moderate significantly in the next 10 years and education and homeland security will become less necessary.

Neither Harris nor Trump have outlined any plan for containing government spending. The old GOP-style of limited government is no longer in vogue for either party. The CBO anticipated rise in Debt/GDP from ~100% to ~122% should be treated as optimistic. A US fiscal crisis looks inevitable.

Of course, there are those who argue debt is simply money. The more US government debt, the more dollars in the world. And the world demands dollars. Until now that has remained true, as evidenced by repeated buying of dollars during periods of elevated global stress.

Unfortunately, the luxury of demand (the exorbitant privilege) has encouraged complacency among American policy makers. Sanctions contradict the fundamental legal sanctity of contract law. Tariff barriers impede both efficiency and exchange of dollars. Protection of Mandatory spending demonstrates to the rest of the world the fiscal fragility of the United States – and its constraint on defence capability.

There are others who point out ‘there is no alternative’. But alternatives are relative, not absolute. The relative attractions of dollar clearly have diminished in the last 15 years, and at an accelerating rate. A viable alternative is not required for the existing dominant currency (the dollar) to become inherently unstable.

It is true there is not much that UK policymakers can do to affect US fiscal outlook. But someone in London should be looking at ways to either shore up the post-WWII dollar system, or to seek an insulation from the effects of its erosion, or to estimate the effects of a shift in investor assumptions about US debt. Who is that person?

We will return to possible effects of this relationship in future posts.

Thanks for reading ExorbitantPrivilege! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.